By Gaby Grammeno Contributor

A Commission has ruled that an employer’s aggressive, confrontational manner while giving feedback left a worker with no real choice but to resign, so his resignation counted as a dismissal under the Fair Work Act.

As a result of the employer’s conduct, the business may now have to defend itself against allegations of unlawful dismissal.

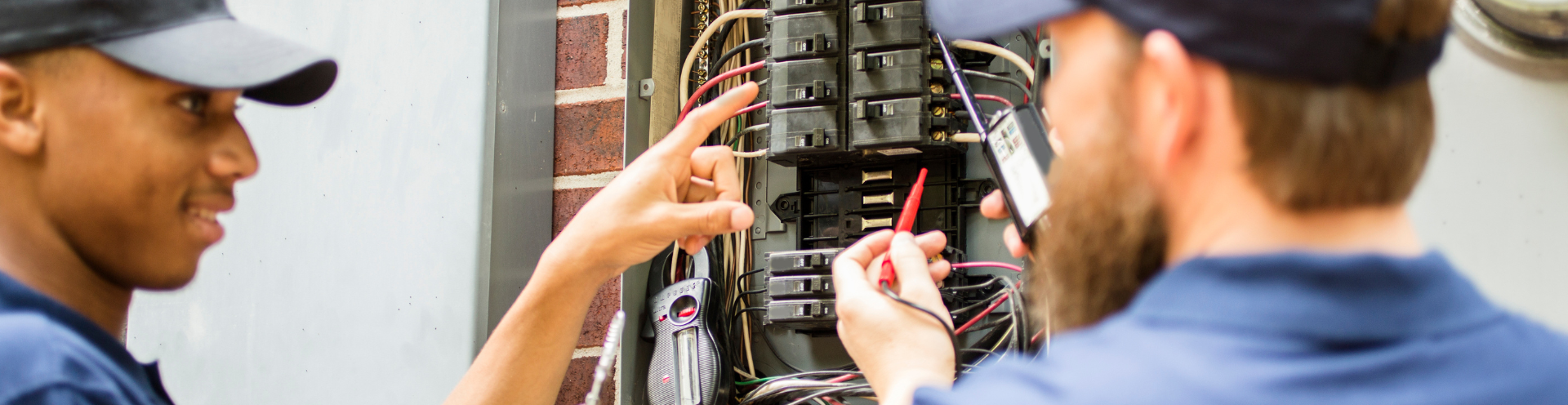

The worker was employed as an electrician with a small business providing electrical maintenance and repairs to housing projects in Victoria.

In October and November 2024, a degree of friction arose between the electrician and the employer with regard to the use of the electrician’s personal phone to contact a client, the thoroughness of his work at the sites he visited, and, without prior agreement from the employer, taking time off work in addition to his lunch break to attend to his religious practices.

In late November the employer emailed the electrician regarding performance issues and arrangements for prayer time, adding an offer to try to help the worker improve his performance in areas lacking.

This was followed by a meeting on 25 November which grew heated, with the employer raising his voice and swearing, accusing the worker of being ‘self-absorbed’ and ‘deceitful’, and saying ‘I don‘t want any negative nancies running around my company fucking becoming toxic to other blokes. It festers. What we do with those people, we fucking weed them out… You need to be on the same page as everyone.’

The next day the worker took a day’s personal leave, texting the employer that ’…my mental health is not in the right place’, and on 27 November 2024, the worker tendered his resignation by letter.

After resigning, the worker made a workers compensation claim for psychological injury, and obtained a report by an independent medical practitioner stating that he had suffered a mental injury and could not return to his job but ‘may have capacity for reduced hours at a different workplace’.

He believed he’d been forced to resign due to various business practices engaged in by the company, and filed a general protections application with the Fair Work Commission.

In the Commission

The employer claimed the worker had voluntarily resigned, and that the employer had not at any stage engaged in inappropriate conduct with the worker.

The Commission’s had to decide whether the electrician had resigned or was dismissed within the meaning of s.386 of the Fair Work Act 2009. Under the Act, if a person is forced to resign because of the employer’s conduct, it counts as a dismissal.

The worker submitted that he was forced to resign because of various things his employer did, including allegedly requiring him to engage in unethical work practices and unprofessional performance management practices.

Abusive behaviour

The electrician’s key contention, however, was that the employer engaged in abusive and bullying behaviour that made him fear for his safety. In particular, he cited the employer’s conduct in the meeting on 25 November.

He submitted a covert recording of that meeting, which he said he’d made because there had been occasions where the employer had allegedly verbally abused him in the past, but it had been in private, with no witnesses.

In Victoria it is not illegal under the Surveillance Devices Act 1999 to record a private conversation, but there is no guarantee that such recordings will be admitted into evidence in the Commission.

In this instance, Commissioner Susie Allison decided to allow it because of its bearing on the case, though she made it clear she’d approach the recording with caution, taking account of the fact that the worker knew he was being recorded but the employer did not.

Commissioner Allison said she did not think the director intended the electrician to resign – she noted that he was ‘clearly an employer who cares about his employees and listens to their concerns’, that he was ‘very open to establishing flexible work arrangements with [the electrician] so he could attend to his religious practices’ and that he provided the worker with a company phone after the worker objected to using his personal phone.

Moreover, the business operated in a ‘blue-collar environment’ where ‘speaking openly and frankly, and swearing is likely to be part of the everyday work culture’.

However, she considered that the language and behaviour directed towards the worker at the meeting on 25 November 2024 is ‘not appropriate or acceptable behaviour in any workplace’.

‘An employer and an employee do not approach each other on a level playing field. An employer is in a position of power and … needs to be aware that behaviour that might be acceptable with a friend or in another context, is not acceptable or appropriate with an employee,’ she said.

She referred in particular to the director’s words ‘Are you fucking serious?’ and ‘You’re making me angry!’ in the context of a raised voice and confrontational tone.

Commissioner Allison found that the director acted in ‘an aggressive, confrontational and inappropriate way that was likely to make [the worker] feel intimidated’, and that the employer’s conduct was such that the worker had no effective or real choice but to resign, therefore he was effectively dismissed for the purposes of s.365 of the Act.

As a result, the matter will now be listed for a mandatory formal conciliation, and if it is not resolved, the worker may choose to pursue his general protections application in the Courts or the Commission.

What it means for the employer

Employers need to be aware that aggressive, confrontational behaviour and language which might be acceptable in another context is not acceptable or appropriate with an employee.

Read the decision

Ali v DMG Building & Electrical Services Pty Ltd [2025] FWC 1244 (2 May 2025)

.png?lang=en-AU&ext=.png)